Anagnostis Aggelarakis has a very interesting piece in Archaeology Magazine detailing his study of a skull from the Greek colony of Abdera. The woman had received a blow by a missile to the back of the head which fractured her skull, but a type of surgery that is first described in the Hippocratic corpus, dating from the 5th-4th centuries BC, was able to save her life. The woman was thus able to live for another twenty years.

Artful Surgery (excerpt):

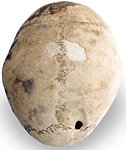

But new evidence, on which the story of the wounded young woman at the head of this article is based, will rewrite our history of the development of ancient medical practice. The patient was among those sent north by Clazomenae, a Greek city in Ionia, to establish a colony at Abdera around 654 B.C. She was successfully treated--a difficult operation performed by a master surgeon saved her--and lived for another 20 years. Her remains, which were excavated at Abdera by Eudokia Skarlatidou of the Greek Archaeological Service and which I have had the privilege to study, provide incontrovertible evidence that two centuries before Hippocrates drew breath, surgical practices described in the treatise On Head Wounds were already in use.

On Head Wounds sets forth diagnostic procedures for identifying and treating a range of cranial injuries caused by different weapons. In most cases, a wound on the back of the head--"where the bone is thicker and oozing puss will take longer to reach the brain"--was less likely to be fatal than one in the front. But, as in the case of the woman from Abdera, "When a suture shows at the exposed bone area of the wound--of a wound anywhere on the head--the resistance of the bone to the traumatic impact is very weak should the weapon get wedged in the suture." So, according to the Hippocratic text, the case was a serious one. It was made more so because of the nature of the weapon, a missile from a sling, because, "Of those weapons that strike the head and wound close to the cranial bone and the cranium itself, that one that will fall from a highest level rather than from a trajectory parallel to the ground, and being at the same time the hardest, bluntest, and heaviest...will crack and compress the cranial bone."

For compressed head fractures, On Head Wounds recommends trepanation, removal of a disk of bone from the skull using a drill with a serrated circular bit. This would eliminate the danger of bone splinters and radiating fracture fissures. It would also permit the removal of bone fragments that had been crushed inward, allowing the brain to swell from the contusion without pressing against loose bone fragments with sharp edges that might puncture the dura mater. But there was one cranial area where a scraping approach was strongly recommended instead of trepanation: "It is necessary, if the wound is at the sutures and the weapon penetrated and lodged into the bone, to pay attention for recognizing the kind of injury sustained by the bone. Because...he who received the weapon at the sutures will suffer far greater impact at the cranial bone than the one who did not receive it at the sutures. And most of those require trepanation, but you must not trepan the sutures themselves...you are required to scrape the surface of the cranial bone with a rasp in depth and length, according to the position of the wound, and then cross-wise to be able to see the hidden breakages and crushes...because scraping exposes the harm well, even if those injuries...were not otherwise revealed."

Faced with a compressed fracture with radiating fissure fractures and fearing damage to the dura mater, the surgeon scraped the bone in length, width, and depth, removing fragments and eliminating the fissures through scraping and not trepanation. He then would have tended to any adjacent injured tissues.

While the reconstruction of the patient's treatment is in part conjecture, based on the Hippocratic text itself, the size and shape of the surgical intervention and use of the rasp rather than trepanation is certain from traces on the bone itself. So the surgical procedure matches perfectly what was recommended two centuries later in On Head Wounds for this type of injury in this location.

We do not know exactly how the Clazomeneans chose the colonists who sailed to Abdera. Were they an elite group, the less wealthy who were willing to risk the venture, or the politically and socially disfavored? We do know, however, that among them there was a masterful surgeon, Hippocrates' predecessor, who was among the earliest of the Ionian school of medical practitioners.

No comments:

Post a Comment