(Updated May 1)

(Updated May 1)The importance of this new paper from the Tishkoff Lab cannot be emphasized enough. It is probably the most comprehensive study of African genetic variation to date. The supplementary material (pdf) is itself 102 pages long and should keep you busy reading for a while (free for non-subscribers).

What this study has found in a nutshell is that "black" Africans belong to 14 distinct clusters. Black Americans belong overwhelmingly to the Niger-Kordofanian cluster, consistent with their origin largely from Western Africa.

The paper covers the levels of diversity in different African populations, finding that:

Within Africa, genetic diversity estimated from expected heterozygosity significantly correlates with estimates from microsatellite variance (fig. S4) (4) and varies by linguistic, geographic, and subsistence classifications (fig. S5). Three hunter-gatherer populations (Baka and Bakola Pygmies and San) were among the five populations with the highest levels of genetic diversity based on variance estimates (fig. S2A) (4). In addition, more private alleles exist in Africa than other regions (fig. S6A). Consistent with bi-directional gene flow (14), African and Middle Eastern populations shared the greatest number of alleles absent from all other populations(fig. S6B). Within Africa, the most private alleles were in southern Africa, reflecting those in southern African Khoesan (SAK) San and !Xun/Khwe populations (fig. S6C) (12). Eastern and Saharan Africans shared the most alleles absent from other African populations examined (fig. S6D).

As I have stated many times before, Bantu speakers have recently expanded from their cradle and contributed genetically to almost all other Africans, while remaining relatively pure in their own homeland:

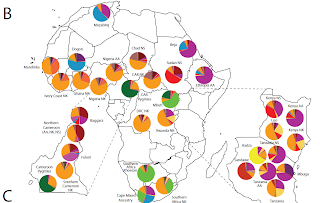

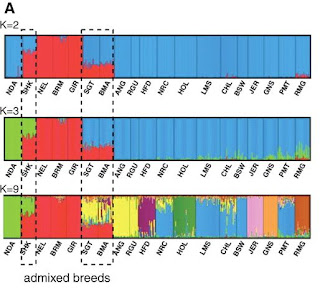

High levels of heterogeneous ancestry (i.e. multiple cluster assignments) were observed in nearly all African individuals, with the exception of western and central African Niger-Kordofanian speakers (medium orange), who are relatively homogeneous at large K values (Fig. 5C and fig. S13). Considerable Niger-Kordofanian ancestry (shades of orange) was observed in nearly all populations, reflecting the recent spread of Bantu-speakers across equatorial, eastern, and southern Africa (26) and subsequent admixture with local populations (27).

Similarly, the high levels of diversity in East Africa are attributable in part to the multiple waves of migration into the region, which occurred in the last 5,000 years, long after the ancestral Eurasians left the continent:

East Africa, the hypothesized origin of the migration of modern humans out of Africa, has a remarkable degree of ethnic and linguistic diversity, as reflected by the greatest level of regional substructure in Africa (figs. S13, S14, and S17 to S19). The diversity among populations from this region reflects the proposed long-term presence of click-speaking Hadza and Sandawe hunter-gatherers and successive waves of immigration of Cushitic, Nilotic, and Bantu populations within the past 5,000 years (4, 28, 31, 37, 38).

The 14 clusters are: Mbugu, Chadic, Saharan Cushitic, Eastern Bantu, NiloSaharan, Saharan/Dogon, Fulani, Western Bantu, S.African Khoesan/Mbuti, Niger Kordofanian, Sandawe, Central Sudanic, Hadza, W.Pygmy.

Table S8 in the supplementary material also allows us to measure the extra-African influences in African populations (and vice versa). Mozabites, for example, from the Sahara are 60.2% "European" reflecting their substantial Caucasoid influence. The Beja possess about a third of this "European" element, the Dogon about 45%. Conversely, low-level African admixture in the Near East consists primarily of the "Cushitic" cluster.

UPDATE I (May 1):

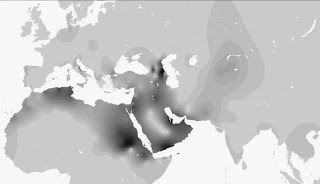

The results of the STRUCTURE analysis on a global level (Figure S10 in the supplementary material provide a visual display of global diversity when seen in an African context. At K=14, there are 10 African and 4 non-African clusters (European, Indian, East Asian, Native American). Contrast between Central-Western and Eastern Africa is the most salient feature of the broad picture, punctuated by interesting mini-clusters formed by Pygmies, Khoi-San and Hadza.

An interesting quote from the paper (AAC=Associated Ancestral Clusters):

The Fulani and Cushitic (an eastern Afroasiatic subfamily) AACs, which likely reflect Saharan African and East African ancestry, respectively, are closest to the non-African AACs, consistent with an East African migration of modern humans out of Africa or a back-migration of non-Africans into Saharan and Eastern Africa.I had pretty much argued as much in the old Dodona forum, that the intermediacy of certain African people between Sub-Saharan Africans and Eurasians was due both to the fact that (a) Eurasians did not originate from Africa in general, but from a specific subset of Africans that was already differentiated from the rest of Africans, and (b) there were back-migrations of Eurasians into Africa.

Related:

- Campbell & Tishkoff review paper on African genetic diversity

- Click language speakers share deep not recent common ancestry

- Male and female genomic contributions to African Americans

Science doi:10.1126/science.1172257

The Genetic Structure and History of Africans and African Americans

Sarah A. Tishkoff et al.

Abstract

Africa is the source of all modern humans, but characterization of genetic variation and of relationships among populations across the continent has been enigmatic. We studied 121 African populations, 4 African American populations, and 60 non-African populations for patterns of variation at 1327 nuclear microsatellite and insertion/deletion markers. We identified 14 ancestral population clusters in Africa that correlate with self-described ethnicity and shared cultural and/or linguistic properties. We observe high levels of mixed ancestry in most populations, reflecting historic migration events across the continent. Our data also provide evidence for shared ancestry among geographically diverse hunter-gatherer populations (Khoesan-speakers and Pygmies). The ancestry of African Americans is predominantly from Niger-Kordofanian (~71%), European (~13%), and other African (~8%) populations, although admixture levels varied considerably among individuals. This study helps tease apart the complex evolutionary history of Africans and African Americans, aiding both anthropological and genetic epidemiologic studies.

Link

.jpg)