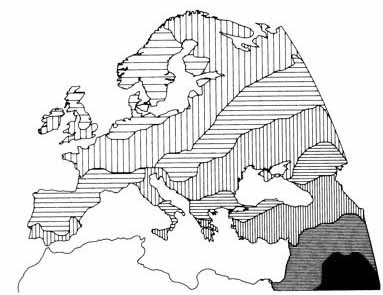

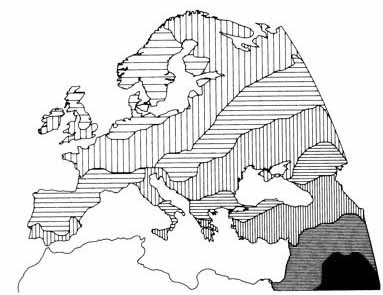

In 1939, Carleton Coon wrote the Races of Europe. In it, he used the "skulls and pots as migrations" paradigm of his times, to infer a number of Neolithic and post-Neolithic migrations into Europe. A map from the chapter on the Neolithic Invasions captures his conception of prehistory well:

This map was drawn before carbon dating had been invented. We now know much more about both the anthropology and archaeology of Europe. But, the main thrust of Coon's prehistorical narrative can be summarizes as arrows on a map, or, prehistory as a series of invasions. The closing paragraph from the Neolithic Invasions chapter sums up this view admirably:

Five invasions, then, converging on Europe from the south and east, brought a new population to Europe during the third millennium B.C., and furnished the racial material from which living European populations are to a large extent descended.

He did think that the Upper Paleolithic population had not disappeared completely, but the name he often used to describe them was survivors, which denoted quite clearly their limited contribution to the present-day population.

When Cavalli-Sforza and colleagues collected genetic data on modern Europeans, and subjected them to principal components' analysis made possible by modern computers, they discovered that the first principal component of genetic variation was oriented on a southeast-northwest axis.

The picture of continuity since the Paleolithic was further supported in the much briefer article by Semino et al. (pdf) on The genetic legacy of Paleolithic Homo sapiens sapiens in extant Europeans: a Y chromosome perspective. This study, based mostly on the observation of rough congruences of the European map with some Y-chromosome markers set the stage for most Y-chromosome work in Europe for the next decade.

In a different study Vanmontfort et al. studied the geographical distribution of farmers and hunter-gatherers during first contact in Central Europe. This contact did not involve either adoption of farming by hunter-gatherers (as in the acculturation hypothesis), or admixture with hunter-gatherers (as in the demic diffusion/wave of advance model). Rather, agriculturalists and hunter-gatherers tended to avoid each other for 1,000 years after first contact!

Acculturation & Demic Diffusion

After WWII, the arrows on a map paradigm was no longer in fashion. The transition from the old to the new prehistory did not happen overnight, but two new intellectual fashions gained ground: acculturation and demic diffusion.

The proponents of acculturation were motivated by a reaction to the pots and skulls paradigm. To the idea that the spread of a new pottery type, or a new type of skull morphology indicated the spread of a people across the map, they countered that (i) pottery could be exchanged, copied, and traded without the movement of people, and (ii) that conclusions based on typological old-style anthropology were unsupportable, and the limitless malleability of the human skull was affirmed.

In some respects, the acculturation hypothesis represented a valid response to the excesses of the pots and skulls tradition. But, they went a bit too far in presenting a picture of complete stasis, in which European people, seemingly fixed to the ground, participated only in "networks of exchange", only ideas and goods flowed, and all differences in physical type across long time spans were ascribed invariably to responses (genetic or plastic) to new technologies, but almost never to the introduction of a new population element.

Demic diffusion is not as extreme as the pure acculturation hypothesis, but it replaces the model of invasions and migrations represented by arrows with a purposeless random walk. Demic diffusion has been argued on both archaeological and genetic grounds.

When Cavalli-Sforza and colleagues collected genetic data on modern Europeans, and subjected them to principal components' analysis made possible by modern computers, they discovered that the first principal component of genetic variation was oriented on a southeast-northwest axis.

At roughly the same time, the widespread dating of Neolithic sites across Europe proved that there was a fairly regular advent of farming, with the earlier sites found in Greece, and the latest ones in the Atlantic fringe and northern Europe.

Demic diffusion was summoned to explain these phenomena. Neolithic farmers, the story goes, did not particularly want to colonize Europe. Europe was colonized as a side-effect of a random process in which farmers moved away from their parent's home, while their population numbers grew due to the increased productivity of the farming economy.

The process was not seen as one of population replacement, however. Rather, it was seen as a slow movement of a wave of advance, in which farmers mixed with hunter-gatherers, and some of them moved on to populate new lands beyond the farmer-hunter frontier. The model predicted that the technology would spread without large-scale population replacement, as the hunters' genes would make a substantial contribution to farmers' gene pools at the furthest end of their expansion.

The Paleolithic Europeans make a comeback

Bryan Sykes' The Seven Daughters of Eve was a popular treatment of a new wave of acculturation-minded scholarship whose more formal expression was the masterful Tracing European Founder Lineages in the Near Eastern mtDNA Pool by Martin Richards et al.

Whereas Cavalli-Sforza and his colleagues had looked at dozens of polymorphisms, their synthetic PC maps of Europe didn't come with dates or easy explanations. The observed clines in Europe may have been due to Paleolithic, Neolithic, or even recent historical events. While they were consistent with the Neolithic demic diffusion hypothesis, the possibility existed that they may have been formed either earlier, or later than the Neolithic.

The new approach by Sykes, Richards, and their colleagues, looked at just mtDNA, but due to its being inherited from mother to daughter without recombination, they could (i) estimate the age of the common ancestors of the "European mothers", (ii) study the patterns of geographical distribution of their descendants to infer when and where they may have lived. Hence, the various stories about Katrine, Ulrike, Helena, etc. in Sykes's book.

The conclusions of the new methodology were clear (at least to the authors' satisfaction):

This robustness to differing criteria for the exclusion of back-migration and recurrent mutation suggests that the Neolithic contribution to the extant mtDNA pool is probably on the order of 10%–20% overall. Our regional analyses support this, with values of 20% for southeastern, central, northwestern, and northeastern Europe. The principal clusters involved seem to have been most of J, T1, and U3, with a possible H component. This would suggest that the early-Neolithic LBK expansions through central Europe did indeed include a substantial demic component, as has been proposed both by archaeologists and by geneticists (Ammerman and Cavalli-Sforza 1984; Sokal et al. Sokal et al., 1991 RR Sokal, NL Ogden and C Wilson, Genetic evidence for the spread of agriculture in Europe by demic diffusion, Nature 351 (1991), pp. 143–144.1991). Incoming lineages, at least on the maternal side, were nevertheless in the minority, in comparison with indigenous Mesolithic lineages whose bearers adopted the new way of life.

The picture of continuity since the Paleolithic was further supported in the much briefer article by Semino et al. (pdf) on The genetic legacy of Paleolithic Homo sapiens sapiens in extant Europeans: a Y chromosome perspective. This study, based mostly on the observation of rough congruences of the European map with some Y-chromosome markers set the stage for most Y-chromosome work in Europe for the next decade.

In today's terminology, this paper suggested that, like mtDNA, most European Y-chromosomes were Paleolithic in origin, and belonged in haplogroups R1b, R1a, and I which repopulated Europe from refugia in Iberia, the Ukraine, and the Balkans, after the last glaciation. To this set were added Neolithic immigrants from the Middle East bearing haplogroups J, G, and E1b1b, and Northern Asian immigrants from the east bearing haplogroup N1c.

Unfortunately, we do not have Y-chromosome data of Paleolithic age to determine the veracity of this scenario. Given present-day distributions, we can be fairly certain of a European origin (but when?) of haplogroup I, of a non-European origin of haplogroup E1b1b (via North Africa or the Middle East), and of N1c. A non-European origin of the entire haplogroups J and G in West Asia also seems quite probable.

The house of cards collapses

The beauty of science is that new data can always falsify cozy and plausible scientific theories. In the case of European prehistory, this occurred due to a combination of craniometric, archaeological, and mtDNA data.

Pinhasi and von Cramon-Taubadel (2009) examined skulls from the early Central European Neolithic (Linearbandkeramik) and found them to be closer to Neolithic skulls from Balkans and West Asia, rather than the per-farming Mesolithic populations.

Our results demonstrate that the craniometric data fit a model of continuous dispersal of people (and their genes) from Southwest Asia to Europe significantly better than a null model of cultural diffusion.

The authors correctly identified their data as rejecting cultural diffusion, but their conclusion that they supported demic diffusion was not warranted as there was really no evidence that Neolithic groups were "transformed" by gradual slow admixture with hunter-gatherers in their march into Europe. Their data could just as easily be explained by plain migration.

Archaeologists also made a strong case for a rapid diffusion of the Neolithic in the Mediterranean. Neolithic settlements appeared suddenly, fully-formed, occupied regions abandoned by Mesolithic peoples, and spread not slowly, in a wave of advance, but rapidly, as a full-fledged colonization:

Thus it appears that none of the earlier models for Neolithic emergence in the Mediterranean accurately or adequately frame the transition. Clearly there was a movement of people westward out of the Near East all of the way to the Atlantic shores of the Iberian Peninsula. But this demic expansion did not follow the slow and steady, all encompassing pace of expansion predicted by the wave and advance model. Instead the rate of dispersal varied, with Neolithic colonists taking 2,000 years tomove from Cyprus to the Aegean, another 500 to reach Italy, and then only 500–600 years to travel the much greater distance from Italy to the Atlantic (52).

To conclude, the following model can be put forward. During the 6th Millennium cal BC, major parts of the loess region are exploited by a low density of hunter–gatherers. The LBK communities settle at arrival in locations fitting their preferred physical characteristics, but void of hunter–gatherer activity. Evidently, multiple processes and contact situations may have occurred simultaneously, but in general the arrival of the LBK did not attract hunter–gatherer hunting activity. Their presence rather restrained native activity to regions located farther away from the newly constructed settlements or triggered fundamental changes in the socio-economic organisation and activity of local hunter–gatherers. Evidence for the subsequent step in the transition dates to approximately one millennium later (Crombé and Vanmontfort, 2007; Vanmontfort, 2007).The "Paleolithic" case won a short-lived victory when Haak et al tested mtDNA from early Central European farmers, discovering that they had a high frequency of haplogroup N1a which is rare in modern Europeans. This finding was interpreted as evidence that the incoming Neolithic farmers were few in numbers and were absorbed with barely a trace by the surrounding Mesolithic populations who adopted agriculture. Acculturation seemed to have won the day! The case was, however, tentative, and hinged on the assumption that the Paleolithic Europeans -who had not been tested yet- would have a gene pool similar to that of modern Europeans.

When hunter-gatherer mtDNA was tested in both Scandinavia (by Malmström et al) and Central/Eastern Europe (by Bramanti et al.), it turned out that continuity from the Paleolithic was rejected. Hunter-gatherers were dominated by mtDNA haplogroup U, and subgroups U4/U5 in particular. None of the other lineages postulated by Sykes et al. as being "Paleolithic" in origin were found in them. Moreover, there was substantial temporal overlap between hunter-gatherer and farmer cultures, but farmers seemed to lack mtDNA typical of hunter-gatherers and vice versa. Confirming the archaeological picture of the two groups avoiding each other, it now seemed that there was little genetic contact between the two, at least in the early age. The Neolithic spread by newcomers; there was no acculturation of Mesolithic people; there was no slow process of admixture between farmer and hunter along a wave of advance.

The gap between contemporaneous farmer and hunter mtDNA gene pools was as large as that found between modern Europeans and native Australians! The whole controversy about the relative contributions of the Neolithic and Paleolithic in the modern European gene pool was found to be beside the point. The modern European gene pool did not seem to be particularly similar to either Paleolithic hunter or Neolithic farmer: it possessed any haplogroups completely absent in pre-Neolithic Europe. And, it did not have a high frequency of the N1a "signature" haplogroup of the Neolithic. Selection, migration, or a combination of both had reshaped the European gene pool from the Neolithic onwards.

Where things stand

We have come full circle. Once again, Paleolithic Europeans assume the status of survivors, as their typical lineages are observed in a small minority of modern Europeans. The evidence for widespread acculturation of European hunter-gatherers or their significant genetic contribution to incoming farmers along a wave of advance is just not there. Hunters and farmers possessed distinctive gene pools, and farmers expanded with barely a trace of absorption of hunter gene pools.

Clearly many details remain to be filled out. What does seem certain, however, is that dramatic events took place starting at the Neolithic, and that modern Europeans trace their ancestry principally to Neolithic and post-Neolithic migrants, and not to the post-glacial foragers who inhabited the continent.

224 comments:

«Oldest ‹Older 201 – 224 of 224Maju,

I meant the language spoken by the original Neolithic settlers in Ireland would have to be gutteral, not Iberian etc...

I can't tell you the number oftimes people have heard me speaking Gaelic and thought it was either Hebrew or Arabic.

"The Celts in Ireland would have conquered the previous Neolithic inhabitants who may have spoken a language akin to Semitic".

Have you got a reference for that? Interesting.

I can't tell you the number oftimes people have heard me speaking Gaelic and thought it was either Hebrew or Arabic.

I can accept that. But it can have a number of explanations, like a substrate influence not in Britain and Ireland but in Central Europe (maybe the Danubian language was related to Semitic after all).

I am aware also of the peculiar Atlantic spread of E1b1b1, which may be of North African origin with stop in Portugal. This could imply some sort of Berberic language area in the Megalithic Atlantic but should, IMO, include at least Portugal and NW Iberia at some point.

But all is highly speculative in any case.

"people have heard me speaking Gaelic and thought it was either Hebrew or Arabic".

I agree that it sounds gutteral, but it reminded me of German the first time I heard it. I'd add that I'm not very familiar with German at all.

Annie,

La Tene Celts brought Indo-European culture to Ireland, and their traces are left in DNA , language and cultural artifacts.

You comment missed the point entirely. It's well known that Ireland was a major source of Silver and Gold to pre-classical Europe, yet I'm not talking about raw material exploitation. I'm talking about the final efflorescence of the La Tene culture, where it reached its apogee in Ireland.

Terry,

I speak Gaelic and German (also French and Latin), and they are not alike at all. When I say guttural, I'm talking about sounds in the back of the throat - like clearing your throat - that are not to my knowledge present in any other European language, including Brythonic Celtic.

Terry,

I;m talking about the "CHHH" sounds, like when you're "hocking a loogie".

See this humorous T-Shirt:

http://www.zazzle.com/chanukah_hocking_a_loogie_t_shirt-235470765193251505

Maju said:

I am aware also of the peculiar Atlantic spread of E1b1b1, which may be of North African origin with stop in Portugal. This could imply some sort of Berberic language area in the Megalithic Atlantic but should, IMO, include at least Portugal and NW Iberia at some point.

You may be onto something with this. Although I am Y-DNA L21+ and M222+, I am mtDNA T1a. As you may know T1a is supposed to have its origin in the Nile Delta area, and spread Westward across the Mediterranean from there... maybe accompanied by E1b1b1??

I;m talking about the "CHHH" sounds...

Do you mean the voiceless velar fricative [x]like the "ch" of "loch"?

If so, it's a relatively common sound, although not too many languages seem to use it at the end of words.

However the Semitic guttural sound is a different sound (or rather array of similar sounds) which is more similar to a very deeply and strongly aspirated [h] sound and is represented by IPA as [H] in its most standard form. This sound and variants does not seem to be found in any European language out of the Caucasus and it is an extremely difficult one to learn in my opinion (specially for smokers).

You may be onto something with this. Although I am Y-DNA L21+ and M222+, I am mtDNA T1a. As you may know T1a is supposed to have its origin in the Nile Delta area, and spread Westward across the Mediterranean from there... maybe accompanied by E1b1b1??

Well, I was thinking rather in NW Africa, where it seemed logical to me that "Cardial" E-V13 would meet "Berber" E-M81 before jumping to West Iberia (and beyond).

I am not sure about T1a but is it found in NW Africa or did it appear to have jumped directly from Egypt to Europe? I don't think that a direct interaction between Western Europe and Egypt could have happened at least before the Bronze Age (probably never).

Maju,

I think, based on the sounds that Gaelic has both. The sentence below is what I'm thinking of:

Chonaic mé, ni fhaca mé ( I saw, I didn't see)

There you have the CH and the FH sounds.

I am not sure about T1a but is it found in NW Africa or did it appear to have jumped directly from Egypt to Europe? I don't think that a direct interaction between Western Europe and Egypt could have happened at least before the Bronze Age (probably never).

Well it could have been involved in Megalithism I guess?

As regards direct contacts between there are architectural and written records to go on. The extreme South West of Ireland was never actively converted to Christianity, by St Patrick or any other missionary. In that area, on the rugged coast there are many anchorite type "beehive huts", similar to those used by Egyptian hermits in evidence. So it would seem that there was a connection between this are and Egypt - or at least the Eastern Med - in ancient times, which brought Christianity to the area.

This area is also the main area of Ireland where E1b1b1 is found.

"Of course La Tene craftsmanship reached its highest expression in Ireland, so virtually no one doubts its connection with Ireland."

Well the Swiss are supposed to be the best chocolate makers but that does not mean they are genetically or even significantly culturally linked to the Amerindians.

And the Romans and Greeks took British copper and tin to make the best metalwork. Does that mean they were British?

Apologies for the double post. There is some kind of lag problem.

PConroy: I fear that your connections with Egypt of all places is feeble. Megalithism? What does Egypt have to do with Megalithism? A single (yet very old) stone ring in Upper Egypt, near Sudan.

I'd consider the known distribution of the clade (which is not well known to me) and ponder whether is a erratic (they are fantastic because you can imagine all sorts of personal migration dventures) or shows a pattern implying populations of some size. If so, which ones. It may be just some sort of Neolithic smaller lineage (I have that impression of T1 but admittedly is vague).

"R1b in the Isles is almost 100% R-L21."

Not according to Family treeDNA. Seems to be a lot of I in there in particular.

http://www.familytreedna.com/public/IrelandHeritage/default.aspx?section=yresults

Maju,

There are a few reasons I say Megalithism for mtDNA T1a:

1. Althought the haplogroup originated in Egypt or surrounding areas - maybe Northern Africa as you nint - it is found at low frequencies today in the Middle East, and at lower frequencies in Scandinavia and Northern Europe. In Central Europe and Eastern Europe people with this haplogroup tend to be Ashkenazim - which I'm not.

2. My T1a matches are some in Ireland, fewer in Britain, most in Northern Germany, Sweden and Finland.

3. In the Isles, T1a is usually associated with Viking descent, and I am a descendant of Normans maternally.

So I think some movement brought T1 or T1a to Northern Europe, where it dispersed from there. Maybe Megalithism brought it to Northern Germany/Southern Denamrk and via the Jasdorf culture or some such it spread??

Why have the Irish such big teeth if they are descended from a population long adapted to agriculture.

Looks to me like having an Eastern origin, either Danubian (earliest aDNA T), from the Pitted Ware Baltic complex (two cases of T) and/or Kurgan (earliest aDNA T1, Central Asia), and then passed to Britain via Anglo-Saxons and Vikings surely.

Megalithism should have spread from SW Europe and Scandinavia was it farthest reach by the NE. If it looks like it went from Scandinavia to Britain and has no connections farther south along the Atlantic, then it's probably not Megalithic-related. However one case of Scandinavian megalithic remains was also unspecified T.

Ken,

I don't think they are.

I think there is a significant substrate of forager/hunter/gatherer.

But I'm guessing the selection against dark skin was much more urgent, then selection for reduced tooth sized.

BTW, my brother has huge teeth, and all my family have very deep rooted teeth, so much so that none of my baby teeth fell out, they all had to be pulled.

Maju,

I think mtDNA T2 seems to have a different distribution in Europe than T1/T1a - and also seems to be the vast majority of T in Europe.

http://dienekes.blogspot.com/2009/10/migrationism-strikes-back.html

http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/pdf/1471-2148-5-26.pdf

The difference between African mt-DNA Hg L3 is ancestor to Asian M., are mutations We see M from L :

Haplogroup L3-e2b – 16189C

Haplogroup M – 16189?

Haplogroup L3-e2b – 16320C

Haplogroup M1 – 16320?

Haplogroup L3-e2b – 16223T

Haplogroup M18 – 16223?

Haplogroup L3-e2b – 195C

Haplogroup M0a – 195?

One test stated I was Sudanese. Another that I was East African.

Just goes to show that the devil is in the details.

Which mutation is East African? Sudanese? West African? Does it really matter?

"Which mutation is East African? Sudanese? West African? Does it really matter?"

It will only depending on what you're trying to do. Maju has a great series of posts concerning mtDNA L starting here:

http://leherensuge.blogspot.com/2010/03/reviewing-mtdna-l-lineages-notes-l0.html

He has placed each haplogroup in its particular region as far as he was able at the time. I'm sure you'll find the posts interesting. He has L3e2b1 as Birkina Fasso and L3e2b2 as egypt and Oman. L3e2 is more widespread.

Post a Comment